What We Know So Far about How COVID Affects the Nervous System

Neurological symptoms might arise from multiple causes. But does the virus even get into neurons?

- By Stephani Sutherland on

Credit: Jian Fan Getty Images Many of the symptoms experienced by people infected with SARS-CoV-2 involve the nervous system. Patients complain of headaches, muscle and joint pain, fatigue and “brain fog,” or loss of taste and smell—all of which can last from weeks to months after infection. In severe cases, COVID-19 can also lead to encephalitis or stroke. The virus has undeniable neurological effects. But the way it actually affects nerve cells still remains a bit of a mystery. Can immune system activation alone produce symptoms? Or does the novel coronavirus directly attack the nervous system?

Some studies—including a recent preprint paper examining mouse and human brain tissue—show evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can get into nerve cells and the brain. The question remains as to whether it does so routinely or only in the most severe cases. Once the immune system kicks into overdrive, the effects can be far-ranging, even leading immune cells to invade the brain, where they can wreak havoc.

Some neurological symptoms are far less serious yet seem, if anything, more perplexing. One symptom—or set of symptoms—that illustrates this puzzle and has gained increasing attention is an imprecise diagnosis called “brain fog.” Even after their main symptoms have abated, it is not uncommon for COVID-19 patients to experience memory loss, confusion and other mental fuzziness. What underlies these experiences is still unclear, although they may also stem from the body-wide inflammation that can go along with COVID-19. Many people, however, develop fatigue and brain fog that lasts for months even after a mild case that does not spur the immune system to rage out of control.

Another widespread symptom called anosmia, or loss of smell, might also originate from changes that happen without nerves themselves getting infected. Olfactory neurons, the cells that transmit odors to the brain, lack the primary docking site, or receptor, for SARS-CoV-2, and they do not seem to get infected. Researchers are still investigating how loss of smell might result from an interaction between the virus and another receptor on the olfactory neurons or from its contact with nonnerve cells that line the nose.

Experts say the virus need not make it inside neurons to cause some of the mysterious neurological symptoms now emerging from the disease. Many pain-related effects could arise from an attack on sensory neurons, the nerves that extend from the spinal cord throughout the body to gather information from the external environment or internal bodily processes. Researchers are now making headway in understanding how SARS-CoV-2 could hijack pain-sensing neurons, called nociceptors, to produce some of COVID-19’s hallmark symptoms.

Neuroscientist Theodore Price, who studies pain at the University of Texas at Dallas, took note of the symptoms reported in the early literature and cited by patients of his wife, a nurse practitioner who sees people with COVID remotely. Those symptoms include sore throat, headaches, body-wide muscle pain and severe cough. (The cough is triggered in part by sensory nerve cells in the lungs.)

Curiously, some patients report a loss of a particular sensation called chemethesis, which leaves them unable to detect hot chilies or cool peppermints—perceptions conveyed by nociceptors, not taste cells. While many of these effects are typical of viral infections, the prevalence and persistence of these pain-related symptoms—and their presence in even mild cases of COVID-19—suggest that sensory neurons might be affected beyond normal inflammatory responses to infection. That means the effects may be directly tied to the virus itself. “It’s just striking,” Price says. The affected patients “all have headaches, and some of them seem to have pain problems that sound like neuropathies,” chronic pain that arises from nerve damage. That observation led him to investigate whether the novel coronavirus could infect nociceptors.

The main criteria scientists use to determine whether SARS-CoV-2 can infect cells throughout the body is the presence of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a protein embedded in the surface of cells. ACE2 acts as a receptor that sends signals into the cell to regulate blood pressure and is also an entry point for SARS-CoV-2. So Price went looking for it in human neurons in a study now published in the journal PAIN.

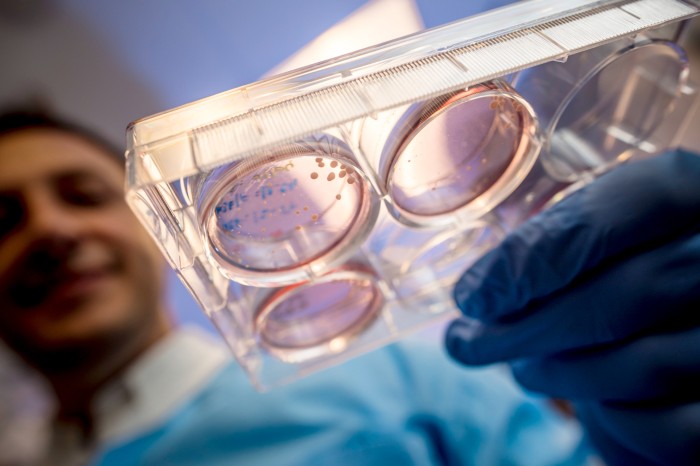

Nociceptors—and other sensory neurons—live in discreet clusters, found just outside the spinal cord, called dorsal root ganglia (DRG). Price and his team procured nerve cells donated after death or cancer surgeries. The researchers performed RNA sequencing, a technique to determine which proteins a cell is about to produce, and they used antibodies to target ACE2 itself. They found that a subset of DRG neurons did contain ACE2, providing the virus a portal into the cells.

Sensory neurons send out long tendrils called axons, whose endings sense specific stimuli in the body and then transmit them to the brain in the form of electrochemical signals. The particular DRG neurons that contained ACE2 also had the genetic instructions, the mRNA, for a sensory protein called MRGPRD. That protein marks the cells as a subset of neurons whose endings are concentrated at the body’s surfaces—the skin and inner organs, including the lungs—where they would be poised to pick up the virus.

Price says nerve infection could contribute to acute, as well as lasting, symptoms of COVID. “The most likely scenario would be that the autonomic and sensory nerves are affected by the virus,” he says. “We know that if sensory neurons get infected with a virus, it can have long-term consequences,” even if the virus does not stay in cells.

But, Price adds, “it does not need to be that the neurons get infected.” In another recent study, he compared genetic sequencing data from lung cells of COVID patients and healthy controls and looked for interactions with healthy human DRG neurons. Price says his team found a lot of immune-system-signaling molecules called cytokines from the infected patients that could interact with receptors on neurons. “It’s basically a bunch of stuff we know is involved in neuropathic pain.” That observation suggests that nerves could be undergoing lasting damage from the immune molecules without being directly infected by the virus.

Anne Louise Oaklander, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, who wrote a commentary accompanying Price’s paper in PAIN, says that the study “was exceptionally good,” in part because it used human cells. But, she adds, “we don’t have evidence that direct entry of the virus into [nerve] cells is the major mechanism of cellular [nerve] damage,” though the new findings do not discount that possibility. It is “absolutely possible” that inflammatory conditions outside nerve cells could alter their activity or even cause permanent damage, Oaklander says. Another prospect is that viral particles interacting with neurons could lead to an autoimmune attack on nerves.

ACE2 is widely thought to be the novel coronavirus’s primary entry point. But Rajesh Khanna, a neuroscientist and pain researcher at the University of Arizona, observes that “ACE2 is not the only game in town for SARS-CoV-2 to come into cells.” Another protein, called neuropilin-1 (NRP1), “could be an alternate doorway” for viral entry, he adds. NRP1 plays an important role in angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels) and in growing neurons’ long axons.

That idea came from studies in cells and in mice. It was found that NRP1 interacts with the virus’s infamous spike protein, which it uses to gain entry into cells. “We proved that it binds neuropilin and that the receptor has infectious potential,” says virologist Giuseppe Balistreri of the University of Helsinki, who co-authored the mouse study, which was published in Science along with a separate study in cells. It appears more likely that NRP1 acts as a co-factor with ACE2 than that the protein alone affords the virus entry to cells. “What we know is that when we have the two receptors, we get more infection. Together, it’s much more powerful,” Balistreri adds.

Those findings piqued the interest of Khanna, who was studying vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a molecule with a long-recognized role in pain signaling that also binds to NRP1. He wondered whether the virus would affect pain signaling through NRP1, so he tested it in rats in a study that was also published in PAIN. “We put VEGF in the animal [in the paw], and lo and behold, we saw robust pain over the course of 24 hours,” Khanna says. “Then came the really cool experiment: We put in VEGF and spike at the same time, and guess what? The pain is gone.”

The study showed “what happens to the neuron’s signaling when the virus tickles the NRP1 receptor,” Balistreri says. “The results are strong,” demonstrating that neurons’ activity was altered “by the touch of the spike of the virus through NRP1.”

In an experiment in rats with a nerve injury to model chronic pain, administering the spike protein alone attenuated the animals’ pain behaviors. That finding hints that a spike-like drug that binds NRP1 might have potential as a new pain reliever. Such molecules are already in development for use in cancer.

In a more provocative and untested hypothesis, Khanna speculates that the spike protein might act at NRP1 to silence nociceptors in people, perhaps masking pain-related symptoms very early in an infection. The idea is that the protein could provide an anesthetic effect as SARS-CoV-2 begins to infect a person, which might allow the virus to spread more easily. “I cannot exclude it,” says Balistreri. “It’s not impossible. Viruses have an arsenal of tools to go unseen. This is the best thing they know: to silence our defenses.”

It still remains to be determined whether a SARS-CoV-2 infection could produce analgesia in people. “They used a high dose of a piece of the virus in a lab system and a rat, not a human,” Balistreri says. “The magnitude of the effects they’re seeing [may be due to] the large amount of viral protein they used. The question will be to see if the virus itself can [blunt pain] in people.”

The experience of one patient—Rave Pretorius, a 49-year-old South African man—suggests that continuing this line of research is probably worthwhile. A motor accident in 2011 left Pretorius with several fractured vertebrae in his neck and extensive nerve damage. He says he lives with constant burning pain in his legs that wakes him up nightly at 3 or 4 A.M. “It feels like somebody is continuously pouring hot water over my legs,” Pretorius says. But that changed dramatically when he contracted COVID-19 in July at his job at a manufacturing company. “I found it very strange: When I was sick with COVID, the pain was bearable. At some points, it felt like the pain was gone. I just couldn’t believe it,” he says. Pretorius was able to sleep through the night for the first time since his accident. “I lived a better life when I was sick because the pain was gone,” despite having fatigue and debilitating headaches, he says. Now that Pretorius has recovered from COVID, his neuropathic pain has returned.

For better or worse, COVID-19 seems to have effects on the nervous system. Whether they include infection of nerves is still unknown like so much about SARS-CoV-2. The bottom line is that while the virus apparently can, in principle, infect some neurons, it doesn’t need to. It can cause plenty of havoc from the outside these cells.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Stephani Sutherland

Stephani Sutherland is a neuroscientist and science writer based in southern California.

Credit: Nick Higgins

Recent Articles

- COVID Can Cause Forgetfulness, Psychosis, Mania or a Stutter

- Mysteries of COVID Smell Loss Finally Yield Some Answers

- Penicillium Fungus Hosts Surprising Opioid Compounds

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-we-know-so-far-about-how-covid-affects-the-nervous-system/